Early Life and Formation

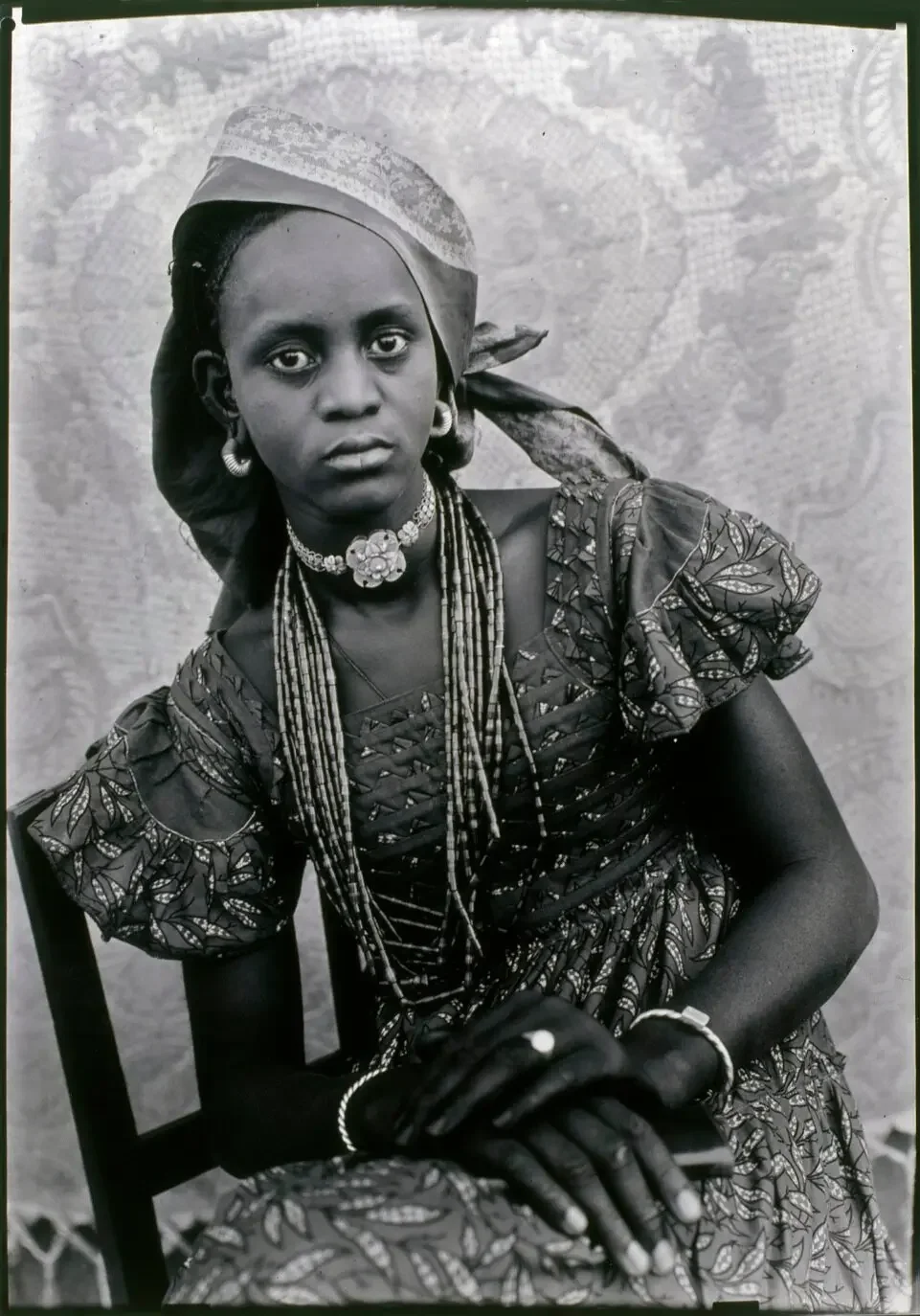

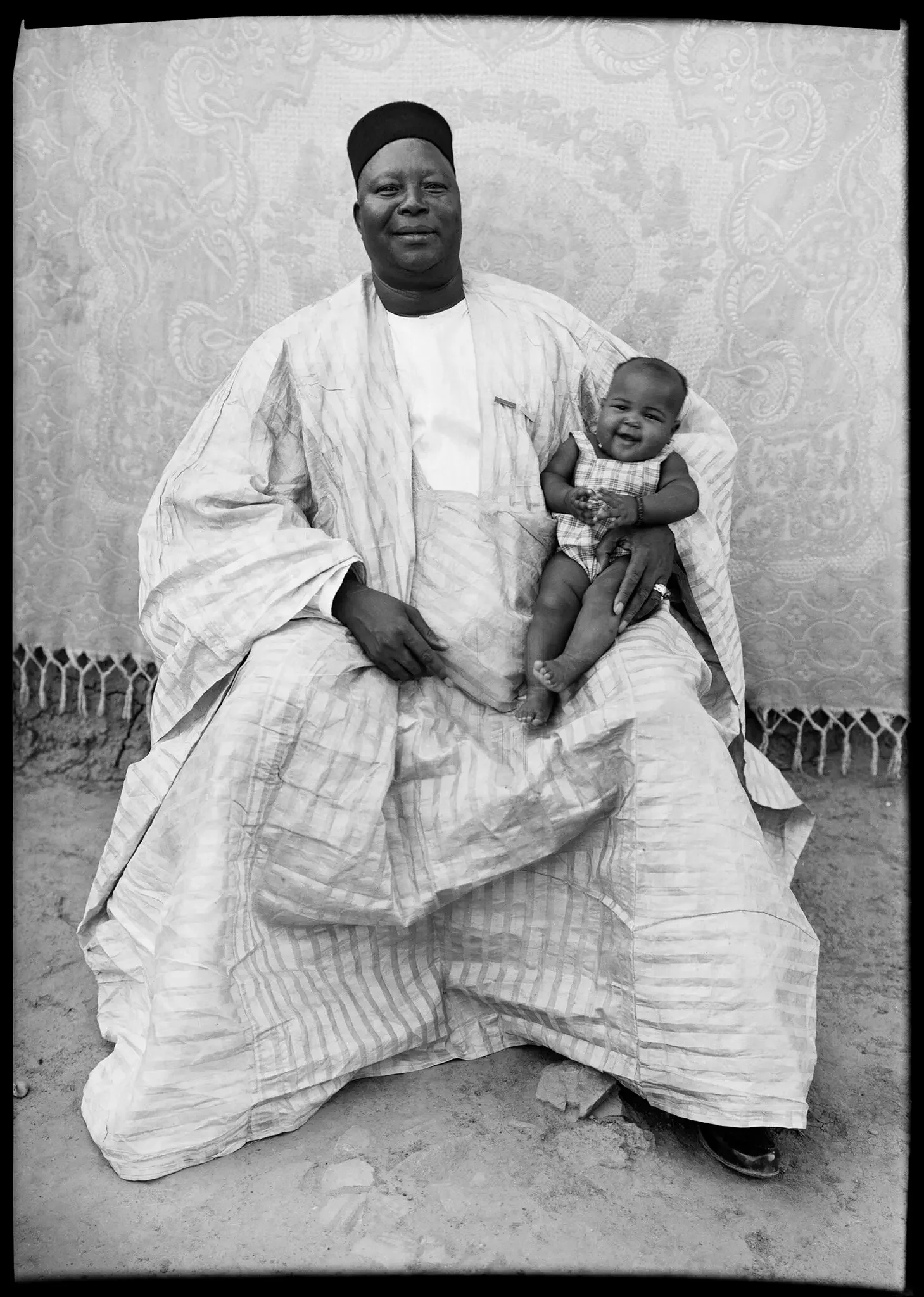

Fela Anikulapo Kuti was born in 1938 in Abeokuta, Nigeria, into radical lineage. His father was a reverend and school principal, but his mother Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti was one of Nigeria's most prominent anti-colonial activists and feminists—a leader who challenged both British colonial rule and traditional patriarchy. This upbringing planted the seeds of Fela's later political consciousness.

In 1958, Fela left for London ostensibly to study medicine, but instead enrolled at Trinity College of Music. There he absorbed jazz—Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Art Blakey—while playing highlife music in clubs with other African students. He formed Koola Lobitos, blending highlife with jazz influences, but his sound hadn't yet found its radical edge.

The American Awakening (1969)

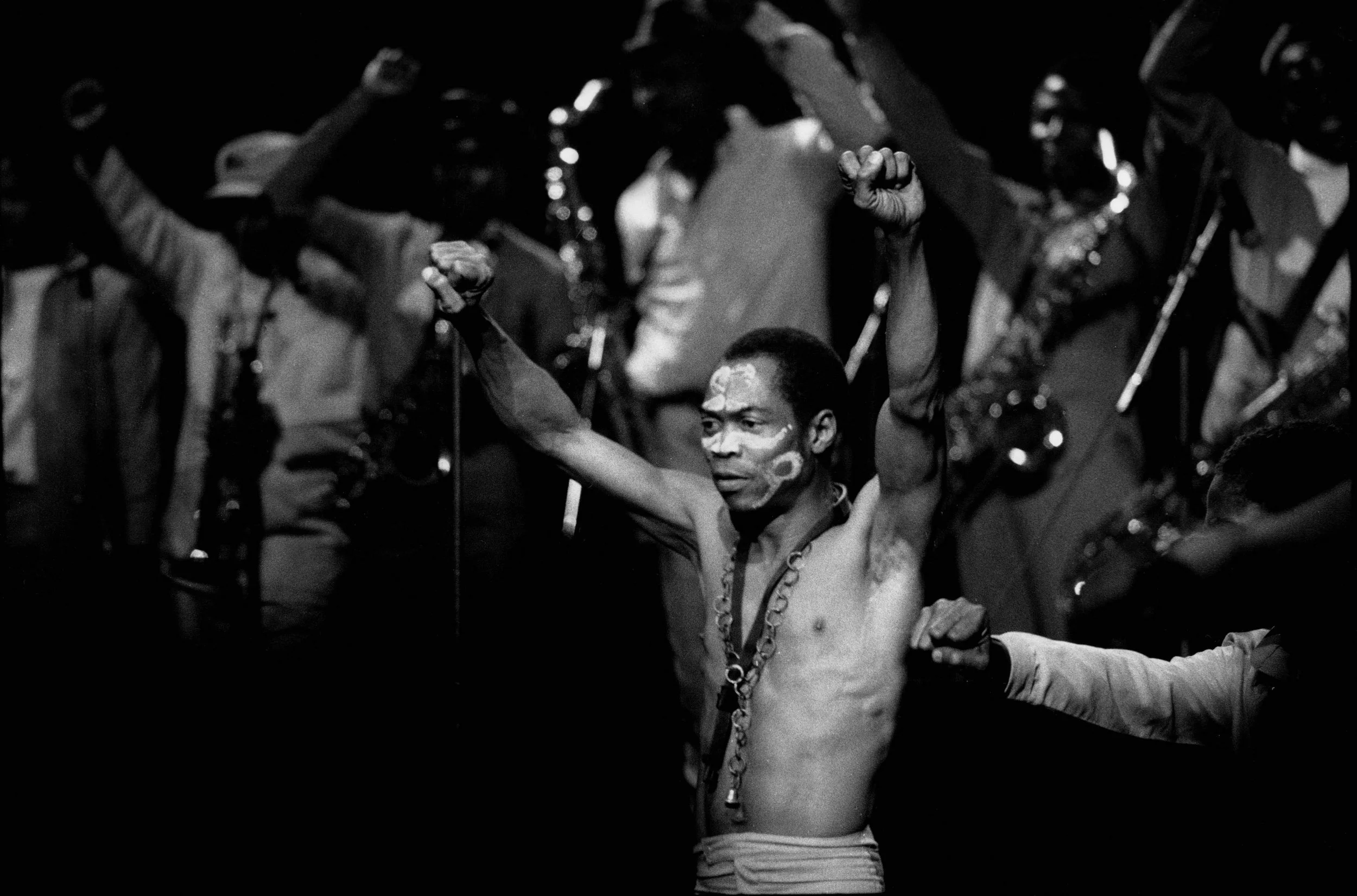

The transformation came in 1969. After returning to Nigeria in 1963 following independence, Fela spent years developing his sound, but the real rupture happened during his band's U.S. tour. In Los Angeles, he met Sandra Smith (later Sandra Izsadore), a Black Panther Party member who introduced him to Malcolm X, Eldridge Cleaver, Angela Davis, and Marcus Garvey.

This exposure to Black Power ideology was explosive. Fela read about the systematic oppression of Black people globally, the concept of mental slavery outliving physical slavery, and Pan-Africanism's call for African unity and pride. He realized that Nigeria's 1960 independence was largely superficial—the country remained economically and culturally colonized. The elite still worshipped Western values while exploiting their own people.

This political awakening didn't just influence his lyrics. It merged with his music in a way that would define the rest of his life.