D’Angelo & Femi Kuti Rehearse “Water No Get Enemy”

There’s a certain kind of magic that only happens in rehearsal rooms — the kind without stage lights, audience applause, or the pressure to deliver anything polished. Just musicians gathering around a rhythm, feeling it out, letting the music tell them where to go.

One of the most revealing moments from D’Angelo’s Voodoo years comes from that kind of room. A rehearsal session captured on shaky footage: D’Angelo sitting in with Femi Kuti and his band, running through Fela’s eternal composition, “Water No Get Enemy.”

If the Soulquarians era was defined by experimentation, spiritual digging, and the rejection of Western metronomic order, this clip feels like a doorway into the very source of that quest.

A Meeting of Lineages

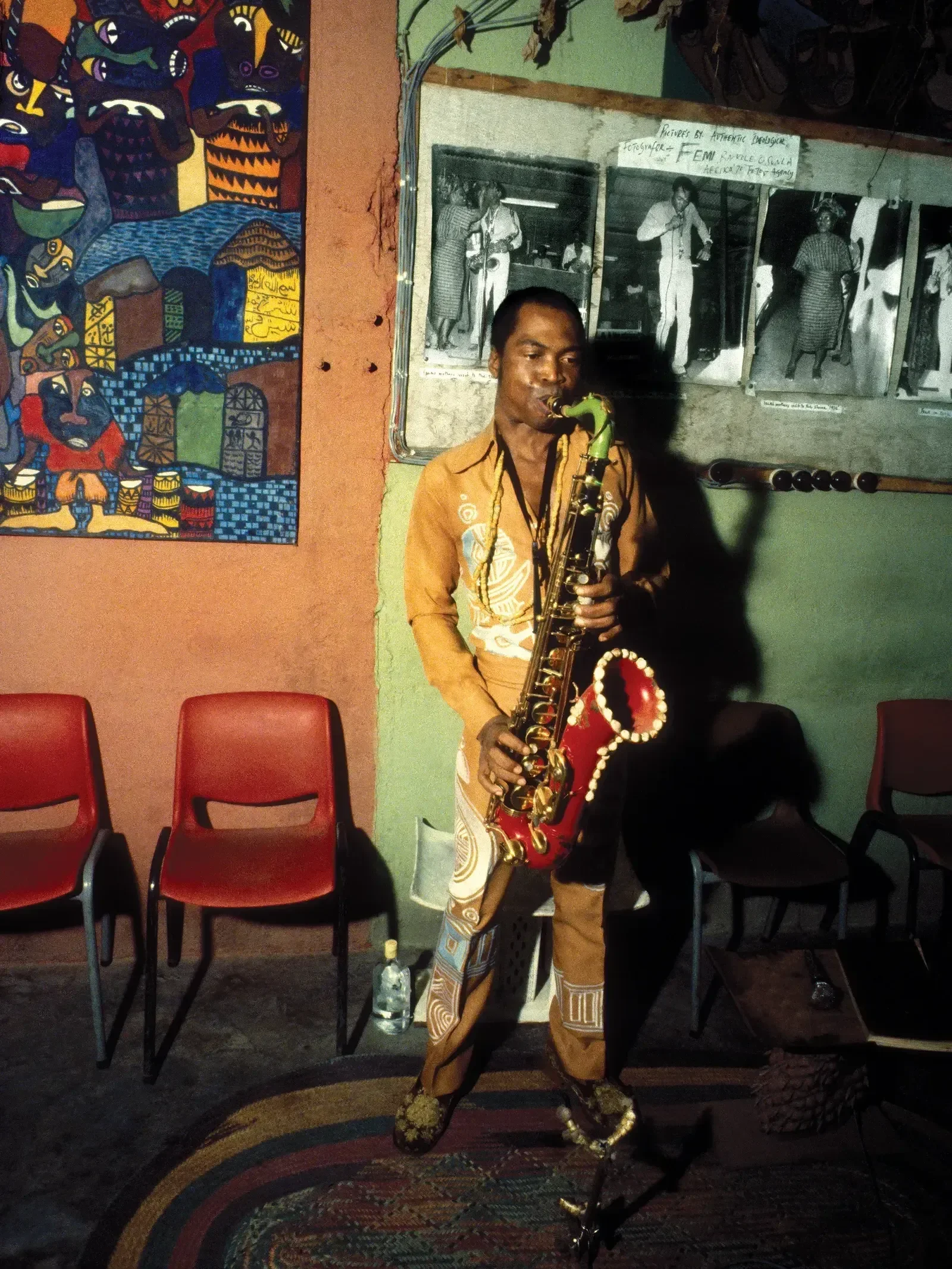

To understand why this moment hits so deeply, you have to understand what “Water No Get Enemy” represents. Written by Fela Kuti during the height of his Afrobeat innovation, the song is both protest and proverb, a meditation on inevitability, persistence, and the unstoppable force of the people. Water is life, and life will not be denied.

Fela built Afrobeat through a fusion of Yoruba rhythms, James Brown funk, Ghanaian highlife, and the political urgency of post-colonial West Africa. It was music meant to shake bodies and systems at the same time.

So when D’Angelo sits in with Femi Kuti, Fela’s son and a torchbearer of that tradition, the room becomes more than a rehearsal space. It becomes a site of exchange where two branches of the same musical family tree finally touching.

D’Angelo’s Return to the Source

During the Voodoo period, D’Angelo was already thinking about rhythm in ways that defied American studio conventions. In Dilla Time, Dan Charnas writes about how D’Angelo viewed time as something that could be felt rather than measured, something inherited rather than learned. This philosophy wasn’t invented in a Soulquarians studio, it came from Black musical ancestry, from drumming traditions older than any genre category.

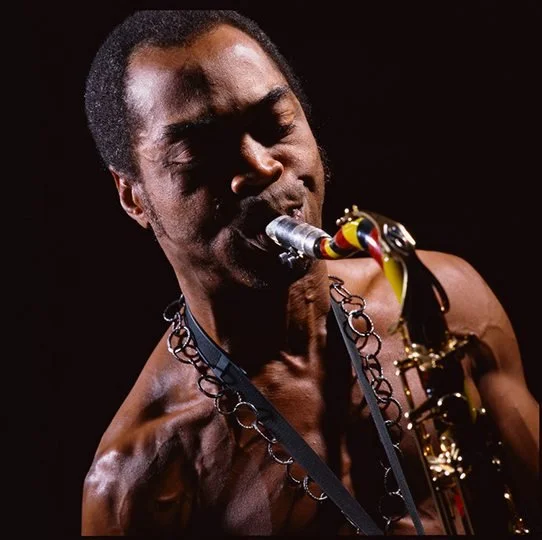

Playing “Water No Get Enemy” with Femi’s band was like stepping directly into that ancestry. No Pro Tools grid. No quantization. No pressure to clean the edges. Everything was organic, elastic, communal.

You see him listening more than playing. Following rather than leading. Trusting the band to hold the center while he floats around it. It’s the same looseness that shaped Voodoo, the same refusal to conform to Western “on top of the beat” expectations. Here, he’s not imitating Afrobeat. He’s responding to it.

The beauty of the clip is in its humility. Nobody is putting on a show. D’Angelo isn’t trying to “prove” anything. Femi and his band aren’t adjusting to impress a visiting star. They’re all simply following the current.

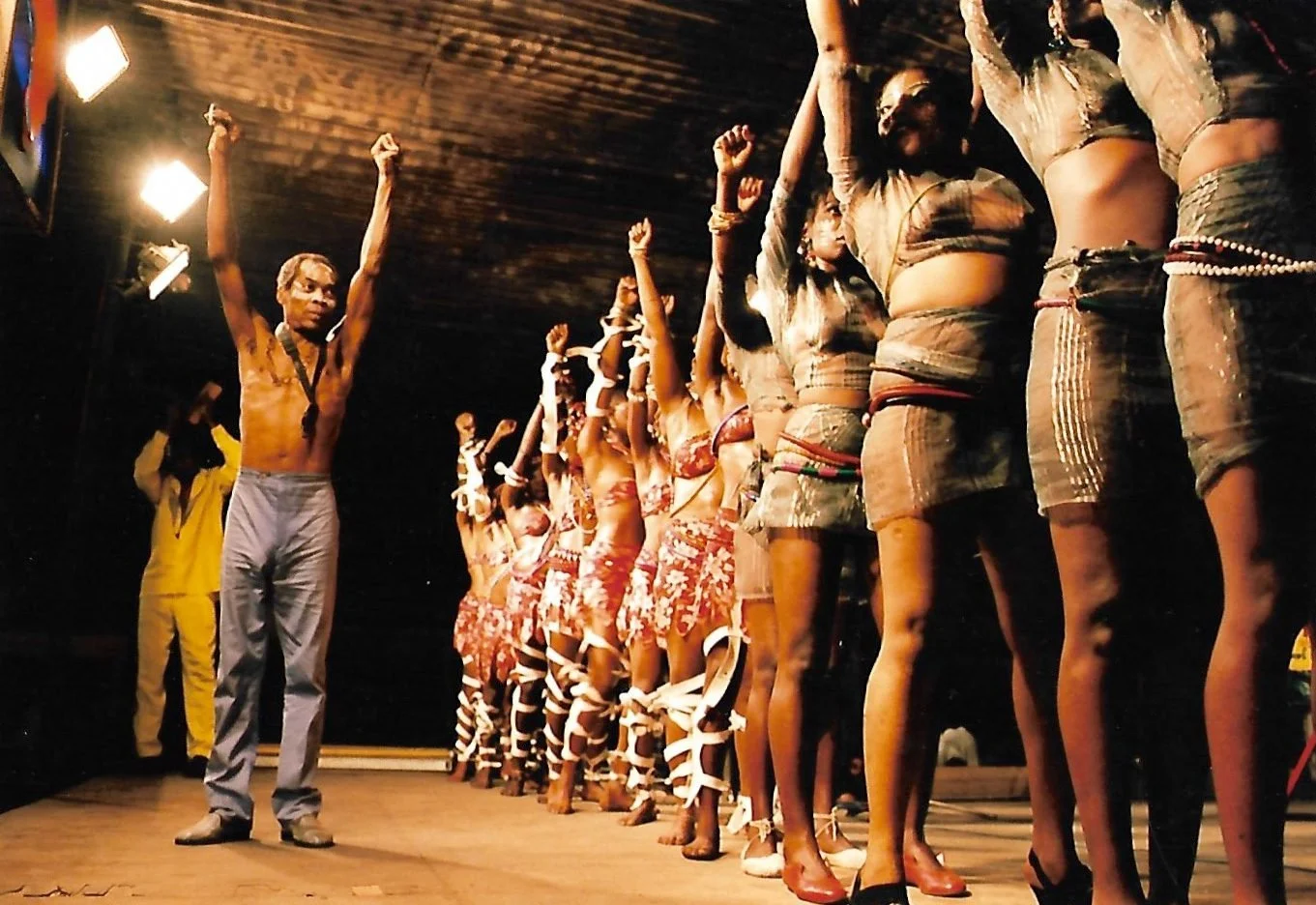

Afrobeat has always been about the collective — the interlocking percussion, the horn stabs, the call-and-response patterns, the repetition that becomes trance. Watching D’Angelo join that ecosystem is watching him submit to something larger than himself.

. . .

For fans of D’Angelo, especially those who trace his spiritual shift from Brown Sugar to Voodoo, this rehearsal session is a Rosetta Stone. It shows his curiosity, his humility, and his commitment to tracing Black music back to its roots.

For those who understand Afrobeat’s revolutionary pulse, it’s equally powerful: the diasporic loop completing a circuit. West Africa to the United States. Funk to soul to Afrobeat and back again. A reminder that these boundaries only exist on maps, not when making the music

And for anyone who loves music, it’s a testament to what happens when artists enter a room with openness rather than ego.